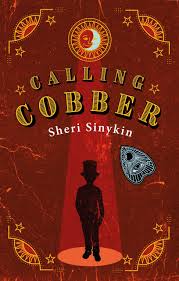

Calling Cobber by Sheri Sinykin, 2020

Calling Cobber by Sheri Sinykin, 2020

Recommended for grades 4-8; realistic fiction, historical fiction

This middle-grade novel set in the recent past (the year 2000, to be exact) is a coming-of-age story about a preteen boy as he struggles with his Jewish identity (or lack thereof) and the reality that his beloved great grandfather might not live much longer. Jacob, usually known as Cobber, is also struggling with the death of his mother six years ago and the impact it has left on his father. In many ways, the themes of mortality and religious identity tie together. Cobber considers himself Jewish by heritage only; he doesn’t really like talk of God and heaven, and he resents any suggestions that he should be going to Hebrew school or getting ready for his bar mitzvah.

In the first chapter, Cobber finds out that his friend Boolkie has given into familiar pressure and agreed to the whole Hebrew-school-and-bar-mitzvah thing. Boolkie’s older brother Eli is about to have his own bar mitzvah, and their parents are so proud that Boolkie just can’t refuse. Although the boys had agreed that they would never go through with it, Boolkie would like Cobber to join him. And Cobber knows that Papa-Ben, his great grandfather, would want him to do his bar mitzvah. So he decides that he just can’t let Papa-Ben know that Boolkie is going to Hebrew school.

Meanwhile, Papa-Ben is suddenly starting to show signs of memory problems. Maybe it’s not surprising, since he’s just shy of a hundred years old, but he’s always been so healthy and independent that Cobber is taken by surprise. Things come to a head one night when Papa-Ben accidentally takes far too many pills and ends up in the hospital. After that, his apartment management doesn’t want to let him move back in, so Dad is considering sending Papa-Ben to a nursing home. Cobber manages to persuade him to let Papa-Ben move into their own home. This sets into motion a series of events that gradually brings Cobber to show a greater interest in his Jewish culture and even the Jewish faith.

Significant side plots include a magic trick act in a school talent show, a few incidents with an ouija board, a school assignment about family history, and a girl from Cobber’s class who clearly has a crush on him. By the end of the book, Cobber has a crush on her, too. While the book explores some meaningful concepts, and there are hints that these side plots are meant to connect to the main themes and ideas of the book, they’re not very well fleshed out. In particular, since the magic act and the ouija board are included in the cover art, I expected them to play a more significant role in the plot.

Overall, this is an interesting book that is worth a read if you’re specifically looking for Jewish-American realistic fiction or a tactful, sensitive portrayal of old age for a middle-grade reader who might have loved ones who are experiencing similar things. But I wouldn’t highly recommend purchasing this book unless you’re specifically looking for one or the other of those niche topics. Of course, with that being said, there isn’t a whole lot of good, mainstream Jewish-American middle-grade fiction. This book might be a welcome addition to library collections for that reason alone, especially because it has a fairly extensive glossary at the end which mostly consists of Hebrew words that have to do with Jewish holidays or religious traditions, the names of traditional Jewish foods, and Yiddish words and expressions.